Key Takeaways

- Cross-examination is one of the strongest tools defence lawyers use to test the Crown’s case.

- The goal is often to expose inconsistencies, bias, or missing details not to “win an argument.”

- Defence lawyers use careful questioning to challenge credibility, memory, and reliability.

- Strong cross-examination can create reasonable doubt by highlighting weak or unsupported evidence.

- Preparation is everything: the best cross-examinations are built on disclosure, timelines, and documented facts.

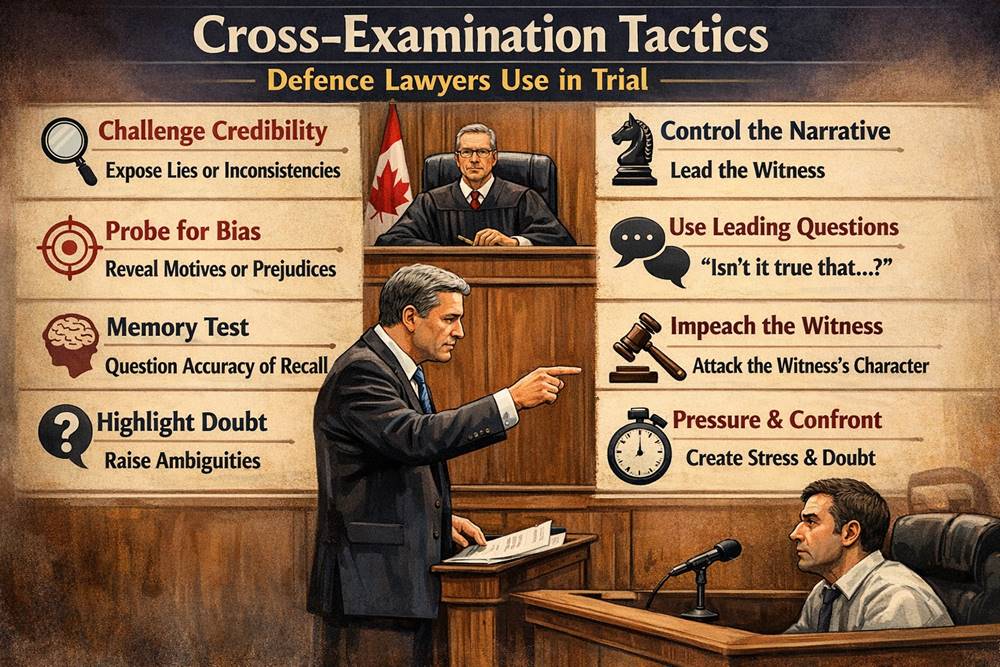

Cross-Examination Tactics Calgary Defence Lawyers Commonly Use

1) The “Yes or No” Control Method

One of the most effective cross-examination tools is control.

In a Calgary criminal trial, the defence lawyer will often use closed questions designed to limit the witness’s ability to wander into explanations, opinions, or emotional storytelling.

That’s why you’ll hear questions like:

- “You didn’t see the beginning of the argument, correct?”

- “You were about 20 metres away, right?”

- “It was dark outside, yes?”

- “You had been drinking, correct?”

Closed questions to limit explanations

Closed questions are typically structured so the witness can answer with:

- “Yes”

- “No”

- “I don’t know”

This matters because open-ended questions allow a witness to expand, add new details, and potentially strengthen the Crown’s case during cross-examination.

Defence lawyers often want to avoid giving the witness that opportunity.

Controlling the pace and structure

Cross-examination is like building a staircase one small step at a time. A Calgary defence lawyer may guide the witness carefully through:

- where they were standing

- what they could see

- what they heard

- what they assumed

- what they later told police

By controlling the pace, the lawyer also reduces the chance the witness starts jumping ahead or giving a “speech.”

Preventing rambling or “new evidence” during cross

Sometimes a witness tries to add extra details that were never mentioned before. This can happen because they are nervous, angry, or trying to be helpful to the Crown.

2) Pinning Down the Timeline

A timeline is one of the easiest places for witness testimony to fall apart.

People often remember the “main moment” of an incident but struggle with:

- what happened right before

- how quickly things escalated

- what happened between two key moments

A Calgary defence lawyer will often press for clear, structured answers about:

- what happened first

- what happened next

- how long it took

Even if the witness is confident, they may not be accurate especially if the incident happened quickly or under stress.

Using time gaps to show uncertainty or assumptions

Time gaps matter in criminal cases. A defence lawyer may expose uncertainty by focusing on questions like:

- “How long was the accused out of your sight?”

- “How long did you look away?”

- “How long between the argument and the physical contact?”

3) Highlighting What the Witness Did NOT See

This is one of the most powerful cross-examination tactics because it shifts the focus from what the witness believes to what the witness actually observed.

A defence lawyer may ask direct questions such as:

- “You didn’t see the first punch… correct?”

- “You couldn’t hear what was said… right?”

- “You didn’t see what happened before the two of them were already close together, correct?”

Showing they filled in blanks with assumptions

Witnesses often want to make sense of what they saw. That’s human nature. But in criminal court, “making sense” can turn into guessing.

For example:

- A witness sees someone fall and assumes they were pushed.

- A witness sees someone holding an object and assumes it was a weapon.

- A witness sees someone walking away and assumes they were fleeing.

A defence lawyer will often highlight that the witness is not intentionally lying they are simply interpreting incomplete information.

And that interpretation can be wrong.

4) Using Prior Statements to Catch Contradictions

One of the most common ways defence lawyers challenge credibility is by comparing what a witness says in court with what they said earlier.

Earlier statements might include:

- what they told police at the scene

- what they said in a recorded interview

- what they wrote in a statement

- what they said in texts or emails

- what they said to another witness

Comparing testimony to earlier statements

If the witness’s story changes, a defence lawyer may ask:

- “Do you remember telling police you didn’t actually see the punch?”

- “Your statement says the incident happened at 1:00 a.m., but today you said 12:30 a.m. Which is it?”

- “You told the officer you were across the street, but today you say you were right beside them. Why has that changed?”

Even small contradictions can matter if they impact identity, intent, or self-defence.

“Refreshing memory” vs. exposing inconsistency

Sometimes witnesses truly forget details, especially if the incident happened months earlier. In that situation, the defence lawyer may use earlier statements to refresh the witness’s memory.

But in other situations, the earlier statement is used to expose that the witness is inconsistent or unreliable.

A common defence point is this:

If the witness was closer in time to the event when they gave the first statement, their earlier memory may be more accurate than what they say in court months later.

Why signed statements matter

Signed statements matter because they suggest the witness had a chance to confirm their account. If they signed a written statement and later contradict it, the defence can argue that:

- the witness is changing their story

- their memory is unreliable

- their testimony is being influenced by emotion, pressure, or discussions with others

5) Challenging Observation Conditions

Even honest witnesses can be wrong if conditions were poor.

This is especially common in Calgary incidents that happen:

- at night

- in winter weather

- in parking lots or outside buildings

- in crowded public spaces

- during fast-moving conflicts

Defence lawyers often challenge factors like:

Lighting, distance, weather, crowding

A defence lawyer may ask about:

- how dark it was

- whether streetlights were working

- whether snow or glare affected visibility

- how far the witness was from the incident

- whether there were other people blocking the view

People often overestimate what they could see in the moment, especially during adrenaline-filled events.

Viewing angle and obstruction

A witness may have been standing at an angle where they could not see:

- hands clearly

- facial expressions

- who made contact first

- what happened behind someone’s body

Defence lawyers often use this to show the witness is confident but their viewpoint was limited.

Intoxication or fatigue

In many Calgary cases involving nightlife, social gatherings, or late-night incidents, intoxication can affect memory and perception.

Even without alcohol, fatigue and stress can cause:

- slower reaction time

- confusion

- memory gaps

- misinterpretation of movement

A defence lawyer may explore whether the witness was:

- tired

- distracted

- upset

- under the influence of alcohol or drugs

Why confident witnesses can still be wrong

Confidence is not proof.

Some witnesses speak with total certainty because they believe their memory is accurate. But memory can be unreliable, especially when a person:

- saw only part of the incident

- felt fear or panic

- discussed the event afterward with others

- watched clips of the incident later

A defence lawyer may argue that the witness is not lying they are mistaken.

And in a criminal trial, being mistaken can be enough to create reasonable doubt.

6) Showing Bias or Personal Interest

Bias does not always mean someone is malicious. It can be as simple as having a personal connection that affects how the witness sees the situation.

Defence lawyers often explore:

Relationship to complainant

A witness may be:

- a friend

- a partner

- a relative

- a co-worker

That relationship can influence testimony, even if the witness thinks they are being neutral.

Personal conflict

Sometimes there is existing conflict between the accused and the witness, such as:

- prior arguments

- workplace tension

- neighbour disputes

- ongoing hostility

Defence lawyers may bring this out to show the witness has a reason to be against the accused.

Financial motive

In some cases, there may be a financial interest, such as:

- a civil lawsuit

- an insurance claim

- a settlement expectation

Even if the criminal trial is separate, the defence may argue that the witness has a reason to support a version of events that benefits them later.

Grudges, jealousy, custody disputes

Some criminal allegations arise from personal or family conflict. A defence lawyer may explore:

- grudges from past relationships

- jealousy

- disputes over parenting or access

- long-term conflict between families

7) Testing Police Procedures and Assumptions

Police officers are trained professionals, but they are not perfect. In Calgary trials, defence lawyers often cross-examine officers to test whether the investigation was thorough and fair.

A defence lawyer may challenge:

Incomplete investigation

Police may have missed steps such as:

- failing to interview key witnesses

- failing to obtain full CCTV footage

- failing to secure evidence quickly

- not documenting important details

If the investigation was incomplete, the defence can argue the Crown’s case is built on weak foundations.

Tunnel vision

Tunnel vision happens when police focus on one suspect early and interpret everything through that assumption.

Defence lawyers may challenge whether police:

- ignored alternative suspects

- accepted the complainant’s story too quickly

- failed to consider self-defence or context

Failure to follow up with other witnesses

If police did not identify or interview other witnesses who were present, the defence may argue that critical evidence was missed.

In busy Calgary areas, there are often other people nearby who could have provided a more accurate account.

Missing notes or missing video collection

Defence lawyers may question:

- missing notebook entries

- unclear timelines

- incomplete reports

- failure to collect relevant video from nearby businesses or buildings

Cross-Examining Different Types of Witnesses

Cross-Examining the Complainant

Cross-examining the complainant is often the most sensitive part of the trial. The complainant may be the person who reported the incident, the person who says they were harmed, or the person whose complaint triggered the charges.

Defence lawyers in Calgary must walk a careful line here: being respectful and controlled, while still challenging the evidence where it is weak or unclear.

Sensitivity + firmness

A defence lawyer does not gain anything by being aggressive for the sake of it. In front of a judge or jury, an overly harsh approach can backfire and make the defence look unfair.

Instead, many experienced lawyers use a tone that is:

- calm

- professional

- firm

- direct

Focus on facts, not emotions

Trials can be emotional, but the verdict must be based on evidence.

Defence lawyers often guide the complainant back to the facts by asking structured questions about:

- where they were standing

- what they saw and heard

- what they did next

- what they told police at the time

This approach helps separate feelings from details. It also makes it easier to identify gaps in memory or inconsistencies in the story.

Highlight unclear memory

In many Calgary cases, the incident happened quickly and under stress. Memory can be affected by:

- panic or fear

- alcohol or substances

- injuries

- confusion during a chaotic moment

- time passing between the event and trial

A defence lawyer may highlight unclear memory with simple questions like:

- “You’re not sure what happened first, correct?”

- “You didn’t see what happened behind you, right?”

- “You can’t say how long it lasted, correct?”

This can create doubt without accusing the complainant of lying.

Highlight inconsistent descriptions

If the complainant’s description changes over time, the defence may focus on differences between:

- what was said in the first police report

- what was said in a later interview

- what is being said in court

For example, inconsistencies may involve:

- how the accused was described

- the order of events

- whether there was a threat

- what words were used

- whether the complainant saw the “first move”

Highlight motive to exaggerate

A defence lawyer may also explore whether the complainant has any reason to exaggerate or frame the situation in a more serious way.

This can include things like:

- personal conflict

- fear of getting in trouble themselves

- protecting their own actions in the incident

- relationship breakdowns or family disputes

- pressure from friends or family

Defence lawyers are careful with this because it can look unfair if handled poorly. But when motive exists, it can be critical to show the jury that the complainant’s version may not be fully reliable.

Cross-Examining Eyewitnesses

Unreliable identification issues

Eyewitness identification is one of the most common areas where mistakes happen.

Defence lawyers may question:

- how far away the witness was

- how long they actually watched

- whether lighting was poor

- whether the person’s face was visible

- whether the witness was distracted or moving

In Calgary, winter clothing can make identification harder because people often wear:

- hoods

- hats

- scarves

- masks or face coverings

A witness may believe they saw the accused clearly, but the defence may point out they were really identifying:

- a general build

- a jacket colour

- height

- or a vague outline

That can be enough to raise reasonable doubt.

Crowd influence

Eyewitnesses are also influenced by crowds. If many people are watching, reacting, or shouting, it can change what a witness believes they saw.

A defence lawyer may ask:

- “Were other people yelling or pointing?”

- “Did you hear someone say ‘he hit her’ before you looked?”

- “Did you see the beginning, or only the middle?”

Crowd influence matters because witnesses sometimes adopt the group’s interpretation, even if they didn’t personally see the key moment.

“Group memory” and assumptions

“Group memory” happens when people talk after an incident and their memories start blending together.

Eyewitnesses may unintentionally fill in blanks by repeating what others said, such as:

- “Everyone said he started it.”

- “People told me he had something in his hand.”

- “I heard she was attacked.”

A defence lawyer may explore:

- whether the witness discussed the incident afterward

- whether they watched a video online later

- whether they read social media posts

- whether they heard rumours before giving a statement

Short observation time

Many eyewitnesses in Calgary cases saw the incident for only seconds.

A defence lawyer may highlight this by asking:

- “You looked over when you heard shouting, correct?”

- “You only watched for a few seconds before looking away, right?”

- “You didn’t see what led up to it, correct?”

If an observation is brief, the witness may have missed:

- the first punch

- who was threatened first

- whether the accused was backing away

- whether someone else intervened

Short observation time is a major reason eyewitness testimony can be incomplete.

Cross-Examining Police Officers

Cross-examining police officers is different from cross-examining civilians. Officers are trained to testify. They often sound calm and confident. They use professional language, and they may rely heavily on notes and procedure.

In Calgary criminal trials, defence lawyers often cross-examine officers to test whether the case was built on solid evidence or on assumptions.

Notebook entries and timelines

A police officer’s notebook can be critical evidence. Defence lawyers often examine:

- the timeline of events

- what the officer did first

- what information they relied on

- what they observed personally versus what they were told

Even small timeline issues matter, especially in cases involving:

- alleged impaired driving

- assault accusations

- weapons calls

- arrest situations in public areas

A defence lawyer may ask:

- when the officer arrived

- when the officer spoke with witnesses

- when notes were made

- whether details were written immediately or later

Notes made later can raise reliability concerns, especially if they were rewritten or based on memory after the fact.

Compliance with rights and procedure

Police must follow rules when they investigate, detain, and arrest people. Defence lawyers often test whether the officer complied with those obligations.

This can include whether the accused’s rights were respected and whether police actions were lawful at each stage.

Questions about detainment, statements, search and seizure

Defence lawyers may ask detailed questions about key moments like:

- detainment

- Why was the person detained?

- What information did police rely on?

- Was the detainment longer than necessary?

- statements

- Did police ask questions before providing legal rights information?

- Did the accused understand what was happening?

- Were statements voluntary, or made under pressure?

- search and seizure

- What legal grounds were used for the search?

- Was there consent?

- Was a warrant required?

- What exactly was searched, and why?

Missing investigation steps

In many Calgary cases, defence lawyers point out investigation gaps, such as:

- failure to interview key witnesses

- failure to obtain full surveillance footage

- failure to collect alternate camera angles

- failure to take photos or measurements

- failure to preserve evidence quickly

This can be especially important when police relied heavily on one complainant’s account or made quick conclusions at the scene.

A defence lawyer may push the officer on whether they considered:

- self-defence

- other suspects

- the possibility of mistaken identity

- alternative explanations

Because if police didn’t investigate those possibilities, the defence can argue the case was incomplete from the start.

Cross-Examining Expert Witnesses

Expert witnesses can sound extremely persuasive in a Calgary criminal trial. They often speak calmly, use technical language, and present their opinions as if they are objective facts. Experts may include forensic analysts, medical professionals, accident reconstruction specialists, or technology-related experts who interpret things like video evidence, digital records, or testing results.

An expert provides an opinion not a guarantee.

The goal is not to disrespect the expert’s credentials. The goal is to test whether their conclusions are reliable, complete, and properly supported.

Limits of expert opinions

An expert’s opinion is only as strong as:

- the information they were given

- the tests they actually performed

- the methods they used

- the assumptions built into their analysis

Defence lawyers often highlight that experts usually do not witness the incident themselves. They may be working from:

- reports provided by police

- witness statements

- selected photos or footage

- lab results

- summaries prepared by others

So the defence may ask questions like:

- “You’re not here to tell the court what actually happened only what your analysis suggests, correct?”

- “Your opinion depends on the accuracy of the information you were given, right?”

What the expert didn’t test

One of the most effective strategies is to focus on what the expert did not examine.

For example, the defence may ask:

- Did you test a second sample or just one?

- Did you review the entire video file or only a clip?

- Did you inspect the original data or just a printed report?

- Did you examine other possible causes or only one theory?

You can’t rule something out if you never tested it.

Alternative explanations

A defence lawyer will often press the expert to acknowledge that more than one explanation may fit the evidence.

For example:

- An injury could be caused by more than one type of contact.

- A behaviour could be consistent with fear, panic, or confusion not guilt.

- A technical result could have innocent causes depending on conditions.

- A video could appear to show something that is actually an angle effect.

Uncertainty vs. certainty

Another key tactic is exposing the difference between what an expert knows and what they believe.

Experts sometimes use confident language that sounds absolute, but real science and technical analysis often includes uncertainty.

A defence lawyer may ask questions like:

- “You can’t say this with 100% certainty, correct?”

- “Your conclusion is based on probability, not certainty, right?”

- “You can’t rule out other explanations, correct?”

Khalid Akram, Criminal Defence Lawyer, is the founding lawyer at Akram Law and has been practicing since 2015. He holds a B.Sc. from the University of Waterloo and a J.D. from the University of Windsor.